View Large

View Large

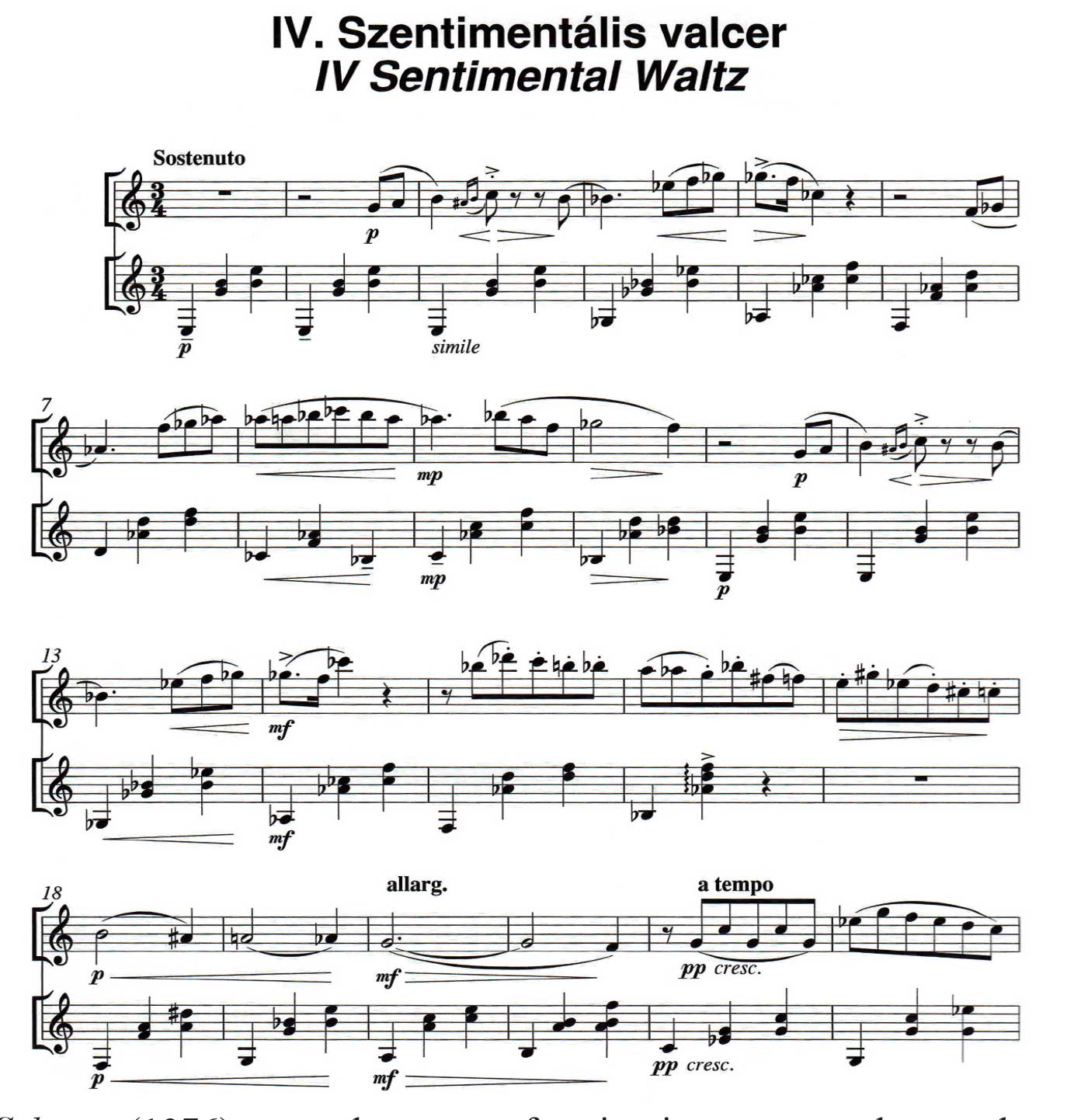

Viktor Togobitsky (1952–1999) was born in Kupino, Siberia. He graduated from the music theory and music history faculty of the Novosibirsk Conservatory in 1971 and earned a degree with honours at the Rimsky-Korsakov State Conservatory in Saint Petersburg (then Leningrad) in 1977. He subsequently came to Hungary through his marriage, where he taught at the Béla Bartók Conservatory and the Liszt Academy Budapest. He was a member of the Young Composers’ Group and the Hungarian Composers’ Union. He was awarded the Erkel Prize in 1998. Most of Togobitsky’s works fall into the chamber music genre. His instrumentation shows the familiarity with the virtues and successes of the Russian school, bringing a new colour into the musical life of Hungary. With his death, the performance of his pieces had diminished – as it is often the case for composers who have recently left the music scene but have not yet made it into musical canon – however, his oeuvre contains many works worthy of recognition. Akkord Music Publishers have mostly published the series which are useful for pedagogical reasons, alongside a solo piece that demands a high level of performing and technical skill. Little Suite (1989) seems to support the notion that the memories of Russian music play a defining role in Togobitsky’s works. Of the five movements of the work, the third bears the title Dumka, a Russian epic or lyric song, and the subtitle Hommage à Tchaikovsky. The ascending melodic line of the fourth movement, Sentimental Waltz, recalls the piece of the same name by the Russian Romantic composer. The approximately ten-minute-long work may be performed on flute or recorder, and guitar.

Scherzo (1976) treats the two performing instruments, the trombone and the piano, as equal partners. Both performers are given soloistic passages. In fact, it is these dialogues that essentially make up the structure of the whole composition, which, by the end of the piece, unites the large leaps of the trombone and the repetitions dominating the piano part in a common musical thought.

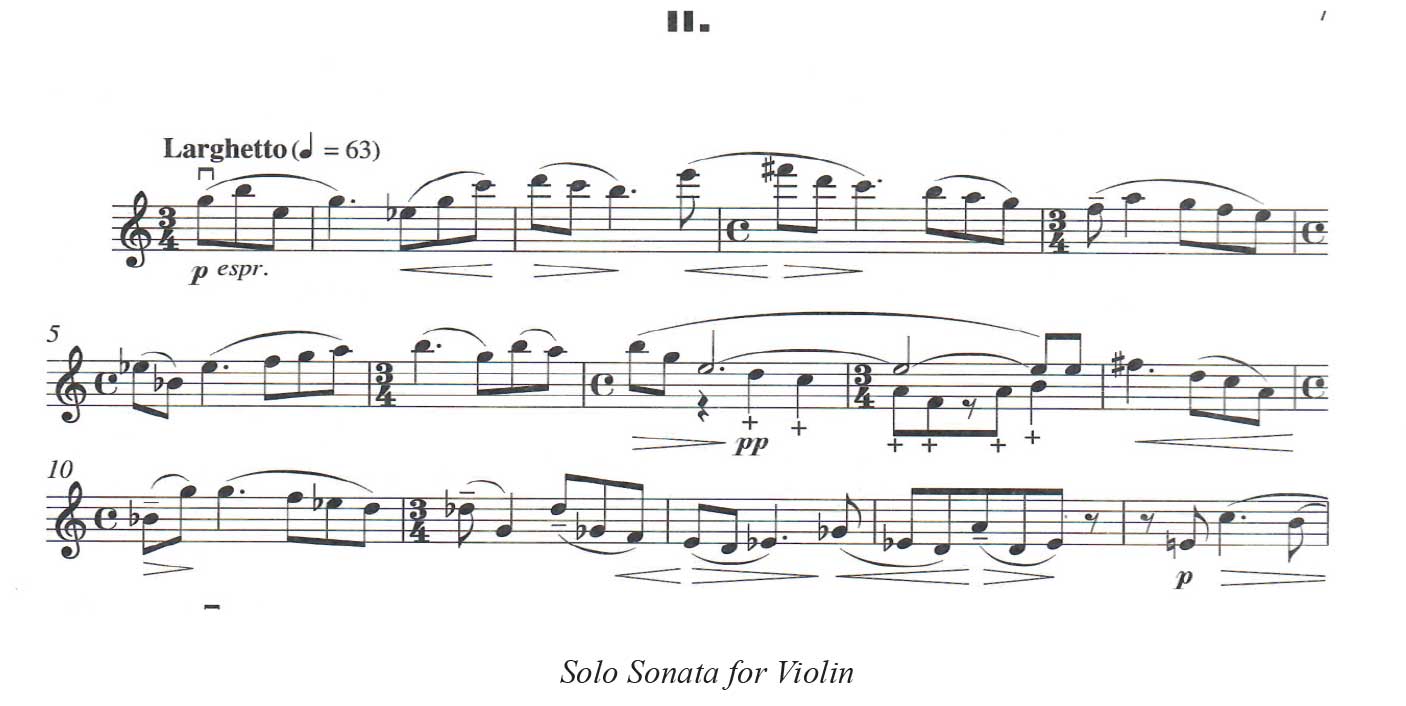

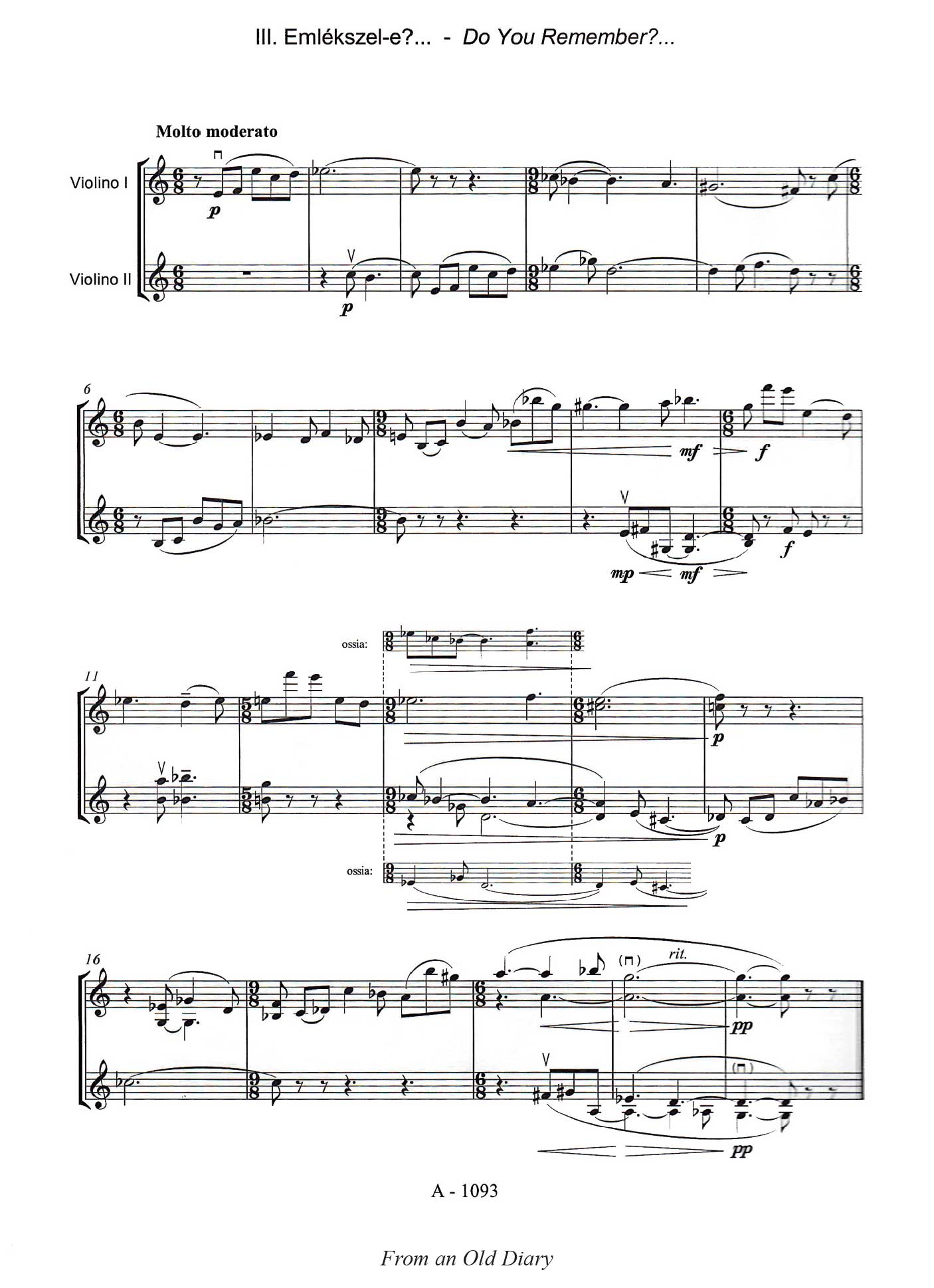

Dedicated to Eszter Perényi, Solo Sonata for Violin (1993) has three movements, the outer ones of which are dominated by energetic, resolute characters (Adagio energico, Allegro risoluto). These dense, weighty sounds and exceptionally virtuosic ornaments and passages are counterbalanced in an almost demonstrative way by the dolce, espressivo characters of the middle Larghetto movement, and the flautando playing technique: it is as if this lyrical movement provided a moment of respite for both music and performer amidst the struggles that require all their strength. Deeply personal notes emerge from between the lines in the piece From an Old Diary (1985) for two violins. The title of the whole series refers to literature, calling up romantic overtones. The series has an educational aim; its character pieces represent different levels of difficulty so that students at music schools may easily find suitable pieces to play. The titles of the pieces, evocative in their conciseness (Moods, Quarrel, Do You Remember?, Morning Stroll, At a Village Feast, Evening Reflection), instantly engage the students’ fantasies, thus finding the appropriate mode of expression among the technical possibilities of the instrument becomes easier or nearly automatic. Children’s Pamphlet (1994) is a collection of pieces with similar character and aim, to be perused by piano students. The thirty-five movements of various levels of difficulty, presenting colourful char[1]acters and phenomena, may even be dubbed Togobitsky’s Mikrokosmos. Certain musical elements almost include extracts of the composer’s works: the seventh piece (Waltz), like the movement from Little Suite, was given the title Hommage à Tchaikovsky, and in Toccata, the restlessly energetic tone of the marcato-rich outer movements of the Solo Sonata is brought back. Some of the movements reflect on the staples of modern technique. such as On a Bike with its calmly rolling eights, or The Robot’s March, in which the jagged intervals are underlined by the marcatos on the primary and

secondary stress of the measures. The interesting harmonies of Solitude, written down without a time signature, evoke a feeling of painful timelessness, and a meditative mood, freely immersed in the sound.

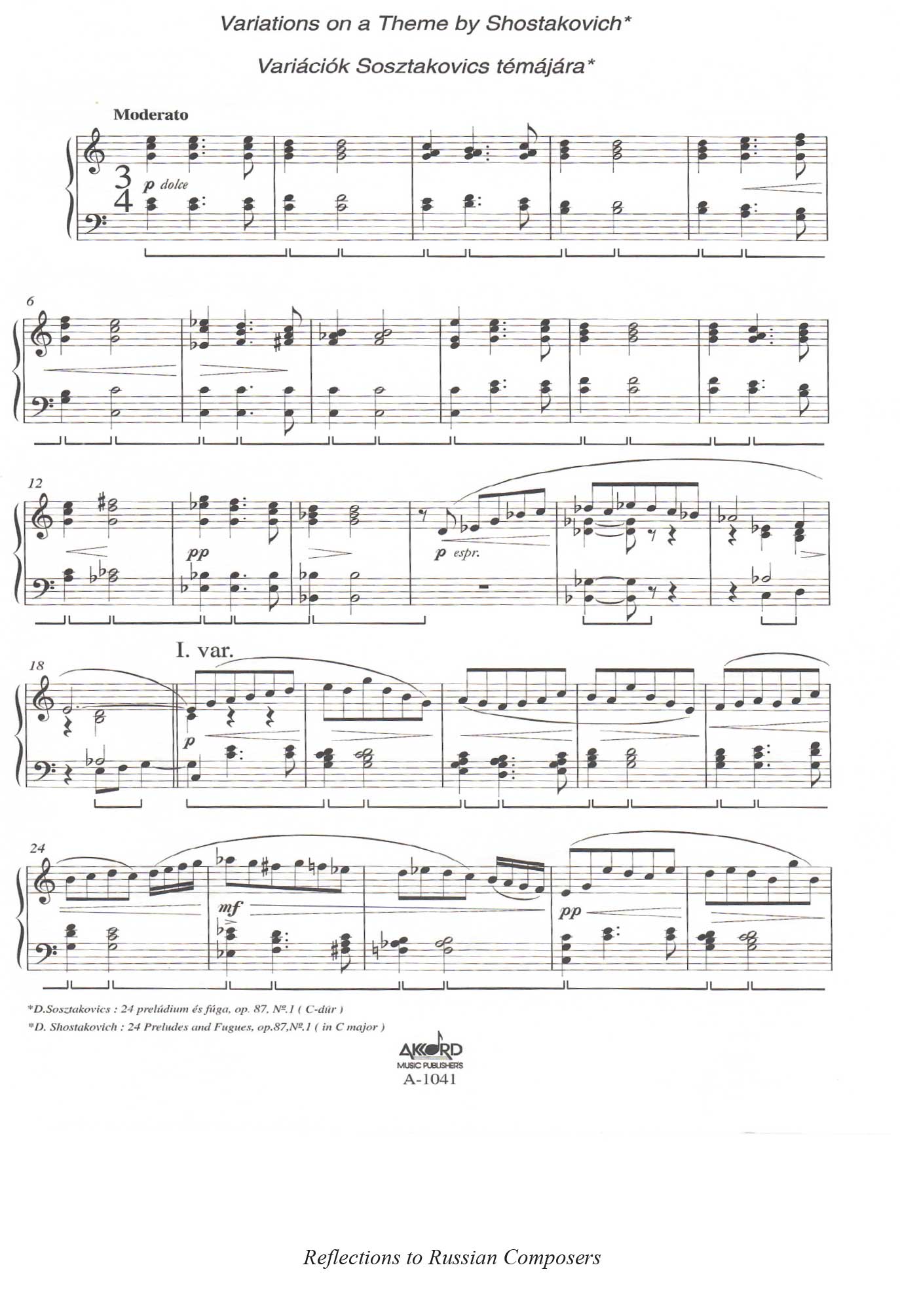

The piano works are complemented by the series Reflections on Russian Composers (1994), in which Togobitsky pays respect to famous composers from his country of birth by presenting several typical musical characters. The first movement (Tempo di marcia), an homage to Prokofiev, may evoke the march from The Love for Three Oranges with its bitter harmonies. Evening Round Dance honours Stravinsky, and even though its sound is of a softer quality than that of the round dance from The Rite of Spring, the thrilling rhythmic combinations are striking. The closing piece of the series is a variation on a Shostakovich theme in waltz-time, the first, C major, piece of the 24 Preludes and Fugues (op. 87). The waltz-rhythm only changes to alla breve in the fourth variation, where the dancelike base character is contrasted by a C minor section (a tempo, funebre) resembling a funeral march.

Written by Viktória Ozsvárt,

translated by Péter Ittzés