View Large

View Large

Iván Madarász (b. 1949) studied composition with István Szelényi at the Budapest Béla Bartók Secondary School of Music, then with Endre Szervánszky at the Liszt Academy of Music. He graduated summa cum laude in 1972. From 1973 to 1980 he taught at the Teacher Training College of the Academy of Music in Pécs. Since 1980 he has been teaching at the Ferenc Liszt University of Music. In 2000 he habilitated and in 2002 he was appointed professor. He is a founding and board member of the Hungarian Composers’ Union. Since 1990 he has been a Board member of the Hungarian Bureau for the Protection of Authors’Rights (Artisjus) and was the chairman between 1995 and 2022. From 1998 he was a curator of the Music College of the National Cultural Fund for two terms. From 2017 to 2020 he worked as consulting editor for the Hungarian Radio. He released seven independent author’s records and a further seventeen of his works were published in CD anthologies. His compositions are regularly played in Hungarian and foreign concert halls and are often performed at various music festivals (ISCM World New Music Days in Sweden and Yokohama, Budapest Autumn, Mini Festival, István Vántus Contemporary Music Days). The most important awards he received as a composer include the Erkel Prize (1992), the Bartók–Pásztory Award (1998), and the Kossuth Prize (2016).

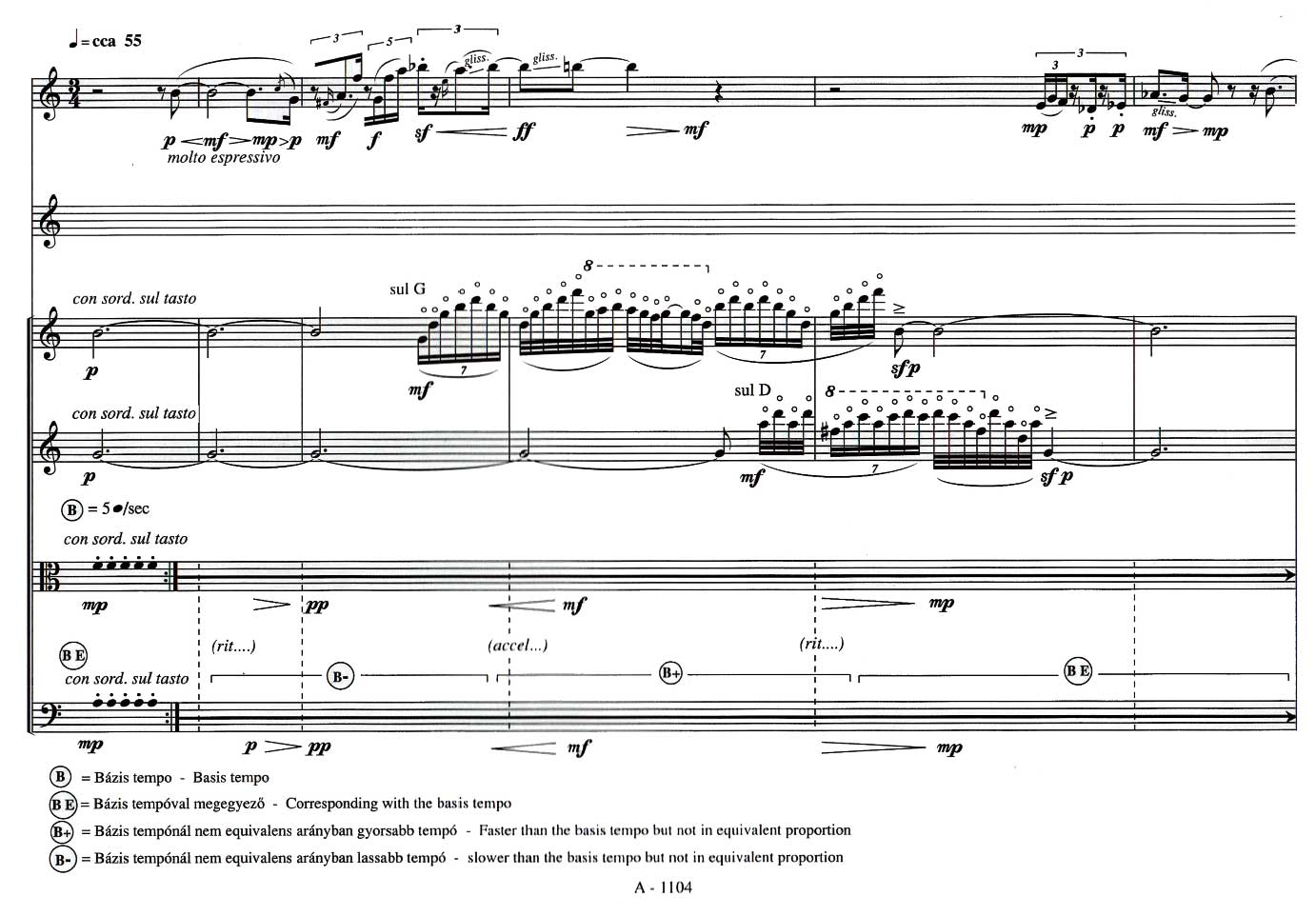

Critics emphasize the dramatic character of Madarász’s music, and the original use of vocal technique and the human voice. Operas are a significant part of his output: the Biblical story of Lot, Prologue, which reflects on Bartók’s Bluebeard, and The Fifth Seal based on a novel by Ferenc Sánta. Hisinstrumental output, especially his worksfor the flute, are characterized by seeking the newest possibilities of instrumental technique. In his chamber works he established a special method for realizing more complex rhythms with non-equivalent ratios. He is also interested in the possibilities offered by electro-acoustic music.

Like most of Madarász’s works, his solo pieces for flute also have several literary and music historical overtones and are characterized by the composer’s openness for new ideas and his empathy. These features are reflected in the pair of compositions linked in their titles to Shakespeare’s tragedy: What Hamlet did not Tell Ophelia (2008), and What Ophelia did not tell Hamlet. The first piece was composed for István Matuz, the second was dedicated to his son, Gergely Matuz. According to the author’s commentary for the first performance of What Hamlet did not Tell Ophelia, he is describing in music Hamlet’s unuttered feelings when contemplating the Shakespearian monologue. The piece be[1]gins with the repetition of a minor third motive which is gradually extended. The initial disquiet by means of the special technical possibilities of the flute (whistle tones and vocalising into the instrument) is almost detached from the dimensions of earthly life, encircled by nightmarish lights. Ophelia’s unspoken monologue is portrayed in a more stable character and motives of a smaller range, as if the composer wanted to depict the maniacal thoughts of the woman arriving at the border of madness. The motives bending down and even tumbling at the end of the piece recall the picture of spiritual and physical annihilation.

FürZOGY for flute solo and Katabasis for flute and synthesiser also form a separate group. The connecting link here is the addressee of the pieces, Zoltán Gyöngyössy. In the texture of FürZOGY the four unorthodox parts are the flute, the human voice, the stamping of feet and key clicks. As a result of this quasi-polyphonic texture, special instrumental effects come into the foreground. The message of the entire composition, however, is at a deeper level; it is not confined to the representative muster of the full technical armoury of flute playing. Katabasis is valedictory music in memory of Gyöngyössy, who died in a tragic car accident. As the composer put it in his comments: “Katabasis is the path which the descending then ascending spirit takes.” This journey is symbolized by the downward, passacaglia-like notes from E’ to B on which the flute builds chords using the tone set of the acoustic scale symbolizing the ascending spirit. Seol evokes similar thoughts. It was written for a unique group of instruments: flute, string quartet and harp. The title is the Hebrew word for the underworld, an underworld which neither rewards nor punishes but can be described as an elysian state, leaving all worldly objects behind. This is the fate of the dead, for ever without destiny. In this sense the work reflects the inspiration of the Nobel-Prize winning novel of Imre Kertész. Peculiar, dream-like combinations of sounds proceed throughout the piece with two allusions to folksongs: “If I Were a Stream” and its melodic relative “The Rooster is Crowing”. The latter melody was connected to the funeral rites of the Hungarian Jewish community in the 19th century.

In addition to the flute, Akkord offers other members of the woodwind family exciting pieces to play. Colla parte for bassoon and piano gives the leading role alternately to the bassoon and the piano, alerting the chamber music partners to constantly listen to each other. Anecdote for oboe and piano was composed as a set piece for a national music competition. The composer’s accompanying statement makes it clear that there is no definite story to search for in the background, it is a work of fiction, a tale without a subject, which appeals to the imagination of the performer and the listener according to the musical expression. There is probably a similar idea behind Three stories composed for the same instruments. The three short movements which follow each other attacca require a lot of imagination, similar to the skill needed for story-telling. The first movement is finished by a cadenzalike section, the second, slow movement has a meditative character and employs aleatory technique: the players freely decide on the order of the motives marked with various letters in the score. There is a similar resolution at the end of In memoriam… (2019). The composition, written for Márk Fülep for alto flute and bassoon, evokes the memory of real and imaginary persons, according to the composer’s notes, and these are reflected in the variety of motives. Even more obvious is randomness in the structure of the trombone and piano piece, Dialogue. In the opening movement the trombone performs its motives numbered 1 to 14 and the piano from A to M in random order, repeating them twice or three times until the trombone has accomplished playing each of the motives at least twice and has given a signal to the pianist to finish playing. In the second movement overtones are played with a special technique and the player sings into the instrument. The special effect in the closing movement is the frequent raising of the back of the tongue. Triptych, also written for the trombone and piano, has an inner ternary structure. Although limited in time and space, aleatory technique is apparent not only in the random order of certain motives but also in free improvisation with the notes of written clusters required within the prescribed rhythm patterns.

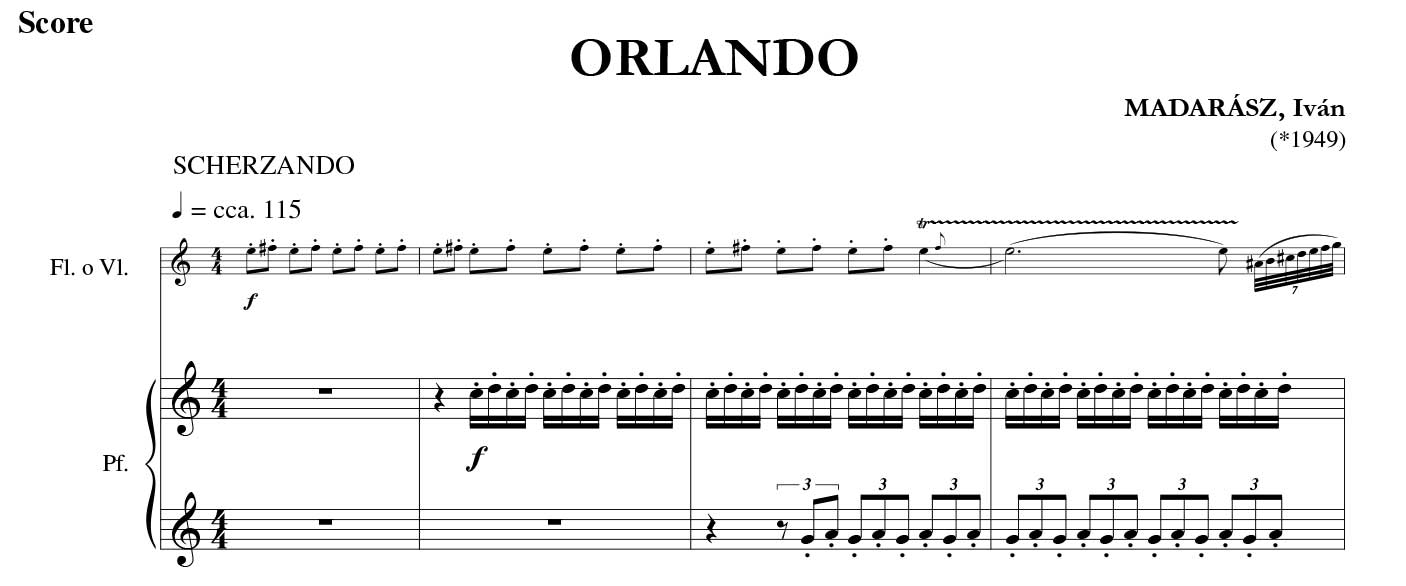

Several of Madarász’s works reflect on the music of earlier ages. Orlando for flute or violin and piano belongs in this group, with reference to Handel’s opera with the same title. The title refers to the fact that the composer uses Handel’s motives but his piece is not a mere variation, since with the free use of Handel’s material a completely new musical idea, an original musical work, is created.

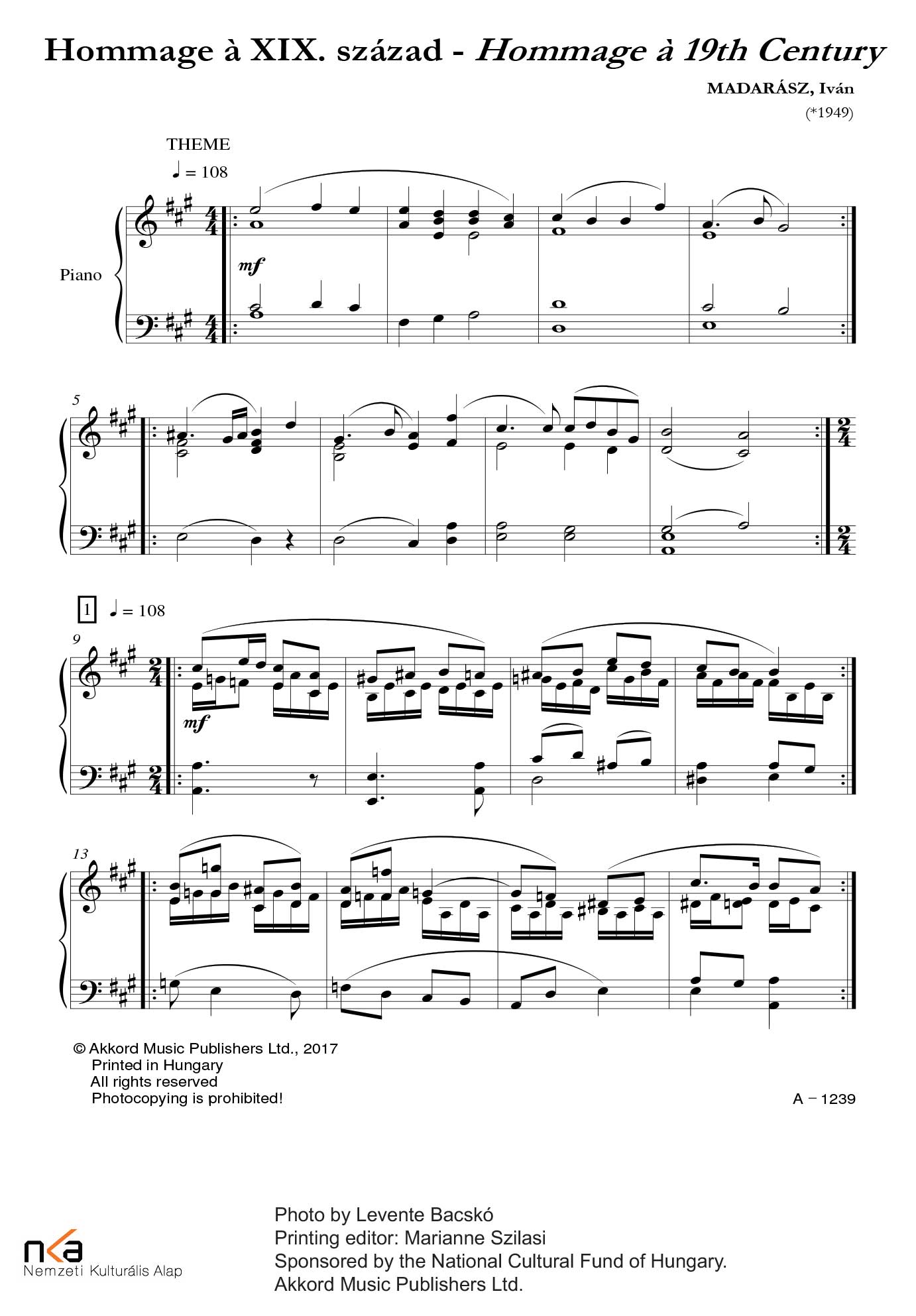

Hommage à 19th Century for solo piano evokes the music of the 19th century in its tone, means and musical style. However, the composer’s aim was not simply to recapture the style: he wanted to realize in practice his own theoretical concept called “horizontal harmony”. The work traverses the territory and history of functional music in the 19th century, the history of the extension of tonality and tonal relationships. New combinations of chords are created from the lower and upper changing notes (minor and major) of the central harmony and their use associates the style of the piece to the music of the 19th century. In due voci and Lot’s Prayer are different in character again, connected by the possibility of a free choice of instruments. The first can be performed on the bassoon or the trombone, the second has even more latitude in its choice of apparatus: it was composed for any wind or string instrument and piano. With the gesture of leaving open the medium of musical transmission, the composer may direct the listener’s attention to the core of the musical message: to a certain extent the instrument that plays the music is irrelevant. In due voci circumnavigates the question of hidden polyphony when one voice creates the impression of polyphony – this is suggested by the choice of title, unusual for a solo work. Lot’s Prayer was originally a part of the opera, Lot. Taken out of the opera and removed from the personality of the human voice, it transmits an eternal musical message.

There are several compositions for larger ensembles in the selection of Akkord Music Publishers. The six-movement Symbols for Roland Szentpáli and the George Solti Brass Ensemble, and Missa brevis composed for soprano solo and three guitars or guitar ensemble, commissioned by the László Szendrey-Karper International Guitar Festival in Esztergom, belong to this group. The latter work has easy playability in view with its clean melodic design and loose accompanying parts. Three Dances in Three-four for two flutes are also characterized by transparent texture. The movements, often leaning towards a waltz, may be included in the teaching material of higher music school grades.

Written by Viktória Ozsvárt

translated by Kata Ittzés