View Large

View Large

Péter Tóth (b. 1965) began his musical studies in the Béla Bartók Conservatory in Budapest as a student of percussion and composition under Oszkár Schwarz and Miklós Kocsár. In 1985 he was admitted into the Liszt Academy of Music, and received his degree in 1990, in the class of Emil Petrovics. In the 1990s, he composed music for theatrical productions in Budapest and other cities and taught at the University of Theatre and Film Arts for years. Currently, he is vice-dean of the University of Szeged Béla Bartók Faculty of Arts. The experimental short film, DenCity 0.37, of which Tóth was composer, co-writer and director, won first prize at the Trenčinska Teplice International Film Festival. In 2006, his choral work Flames won second prize at the com[1]poser competition of KÓTA in memory of the 1956 revolution. In 2008, another choral work of his, …canticum novum, received the special prize in Jihlava (Czech Republic). His piece for mixed choir, Hymnus ad galli cantum, earned him the Diapason d’or prize, and in the same year, he received KÓTA’s prize for his achievements in the field of choral music. He was the winner of the composer competition organized in 2010 by KÓTA for the two-hundredth anniversary of Franz Liszt’s birth. In 2017, he received the award of the European Choral Association for his composition Tale-Box. In 2007 he was awarded the Erkel Prize and in 2013, the Bartók–Pásztory Award. He is a regular member of the Hungarian Academy of Arts.

As a composer, Péter Tóth professes that “music must be about something”. He does not believe in so-called “absolute music”, however, in his view, programmatic music does not simply entail the concrete meaning carried by each motif, but rather the conceptual background of the piece, a basis that can be expressed in words. His titles often refer to the music of earlier periods, or the characteristic features of popular music. The references, however, do extend beyond the titles, into the domain of musical material – a clear example being his 2009 opera, The Hammer of the Village, whose numbers were each written in the style of a different composer. Frequent harmonic changes, the importance of the melody, and the preference of expressing emotions to structural solutions are all characteristic of his music.

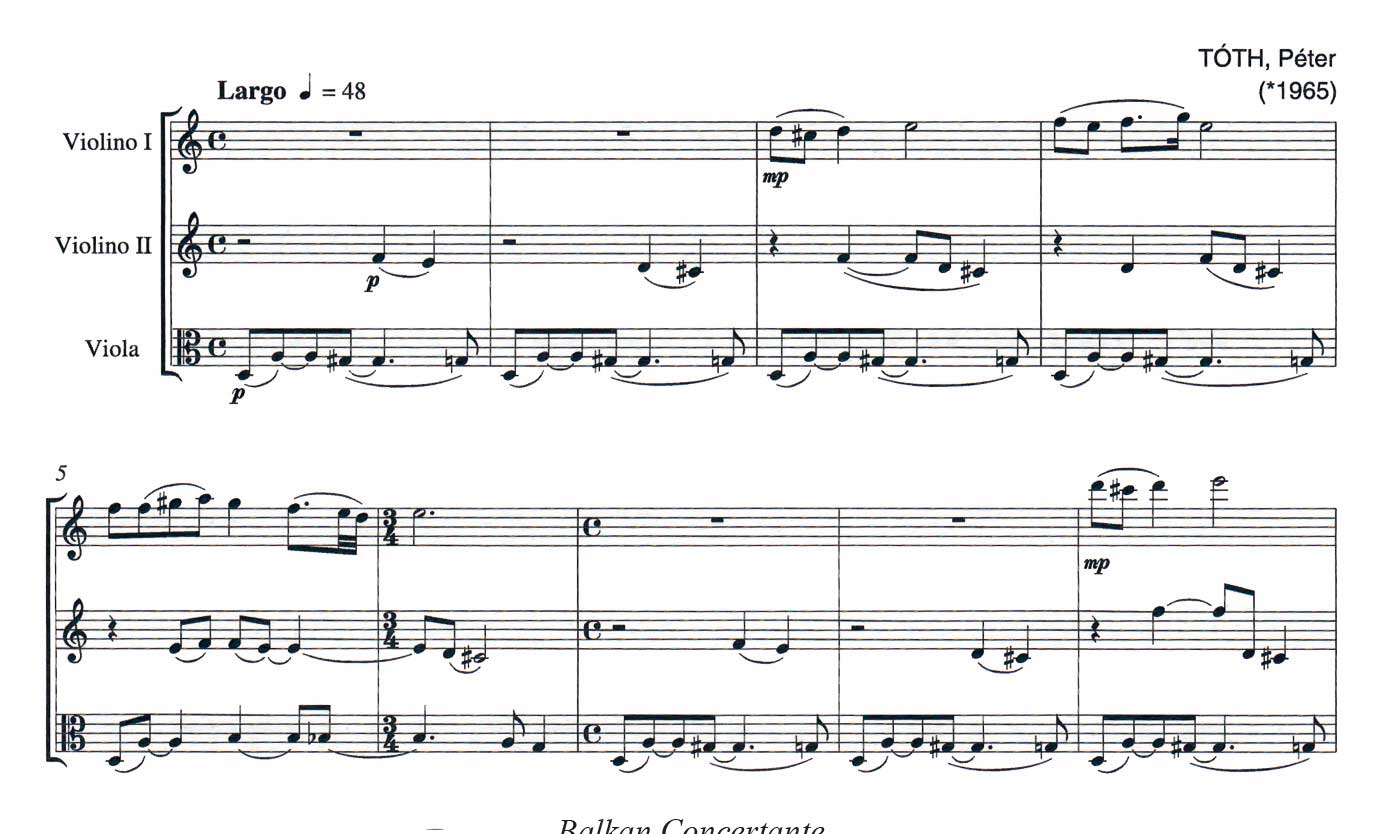

Bird-Trap (2005) is a fantasy-like composition for recorder, around four minutes in length. The introduction (Largo, libero), fundamentally slow in its beat, but with ornaments resembling birdsong, is followed by a section whose texture is made up of sixteenth notes. Towards the end of the piece, the thematic material of the introduction is recalled for a few measures, then, after a trill, a frullato glissando depicts the bird capriciously flying away. Another piece for solo instrument is The Last Letter of Cyrano de Bergerac (2002) for cello. Written for György Déri, the piece exploits the possibilities of the instrument while staying within the realm of traditional instrumental technique. The piece is characterized by a wide spectrum of dynamics, a range of pitches that covers the entirety of the instrument, and occasional passages that demand virtuosic technique. Three large sections may be distinguished in the structure of the piece. The first one (Andante, parlando) is a monologue that unfolds from sigh-motifs and is dominated by arpeggiated chords. In the second part (Andante cantabile), the prominence of the broken-up chords remains, but the flow of the music becomes smoother, more song-like. Putting an end to the piece – and the imaginary letter – is a fast, heated section (Allegro assai), which brings linear thinking into the forefront, its character defined by march-like rhythms and chromatic runs. The ending, however – evoking Wolfram’s song to the evening star – is as if it was uncertain about the content of the letter: the G held above the movement of C-G in eights creates a feeling of a half cadence while closing – or rather cutting off – the piece.Duo concertante (2005) for two violins and Balkan concertante (2007) for two violins and viola are not only similar in their title, but the required level of technique – both chamber pieces are appropriate for the use for students in the higher grades of music schools and concert artists alike. While Duo concertante suggests precursors from Baroque music, the melodies of Balkan concertante are an adaptation of authentic folk music from the Balkans.

Apocryphal Sonata, true to its title, is in some sense a piece that conceals itself. It begins with twenty-five measures of violin or cello solo (Parlando con moto), then, in the Allegro, a single extensive sonata form is built with three distinct themes.

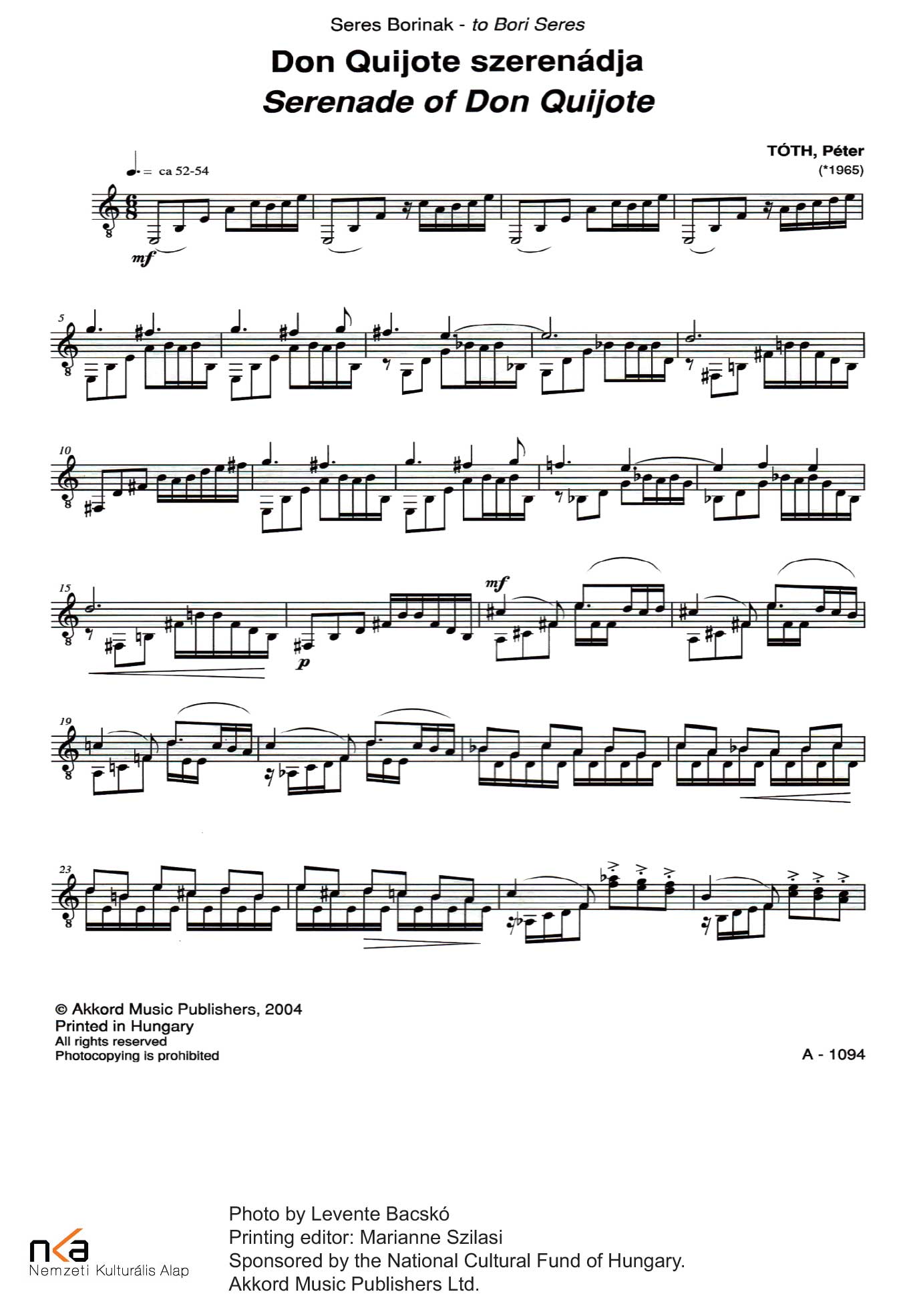

The two pieces for solo guitar composed in 2001 were published in a single volume by Akkord Music Publishers. The titles of both works refer to the sister arts: Serenade of Don Quijote evokes Cervantes’s classic, while Letters for na’Conxipan is a reference to the imaginary world invented and painted by Lajos Gulácsy. Both pieces can be used as study material from the higher grades of music school. With their help, the instrumentalist can almost unconsciously acquire technical skills like clearly emphasizing the relation of melody and accompaniment, smooth legato playing, and thinking in terms of large forms within a metrically varied material.

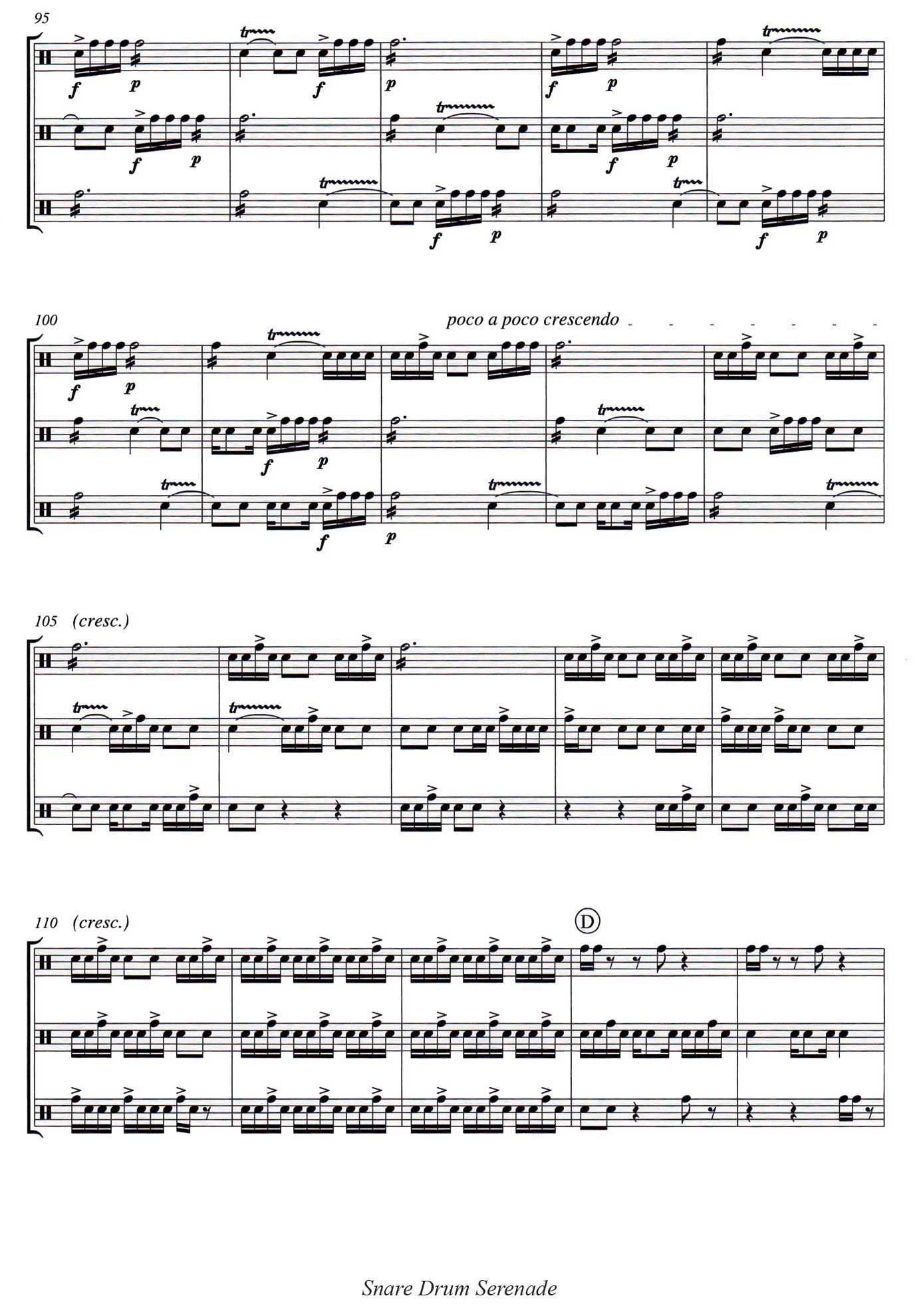

The Hungarian title of Snare Drum Serenade (Zsoldos szerenád, 2002) is a nod to Soldier’s Serenade, the alternative title of Lassus’s Matona mia cara. Since it was written for three snare drums, it is defined by the combinations of rhythms rather than a melodic line. The seemingly simple composition – only containing the most basic rhythms (fourths, eights, sixteenths) – often tricks even experienced performers.

Written by Viktória Ozsvárt,

translated by Péter Ittzés