View Large

View Large

Máté Hollós (*1954) studied composition at the Budapest Liszt Aca[1]demy with Emil Petrovics graduating in 1980. Between 1980 and 1989 he worked for the copyright society, Artisjus, promoting Hungarian music abroad. From 1982 to 1990 he also taught foreign students at the Liszt Academy. In 1989 he founded Akkord Music Publishers, which was the first private music publishing house after the 40-year monopoly of Editio Musica Budapest. In 1990 Hollós became editor responsible for classical and folk music at Hungaroton record company; From 1993 he was managing director of Hungaroton Classic, then of Hungaroton Records, nowadays acts as general director of Hungaroton Music PLC. Between 1990 and 1994 Hollós was board member of the Hungarian Composers Union, of which he became president in 1996 and honorary president in 2021. He has also been president of the István Vántus Society since 1996. He has been the vice president of the Hungarian Music Council since 2012 and a board member of Jeunesses Musicales Hungary and the Hungarian Art Music Society. He has served on the board of Artisjus since 1999. Hollós has taught courses about copyright issues at the Liszt Academy of Music since 2013. Since 1980 he has been publishing articles in various music and art periodicals, has pre[1]sented radio programmes and published three books. The International Society for Contemporary Music made a film portrait of him in 1986. He has received several honours for his work: the audience prize of the Rostrum of New Music of the Hungarian Radio (1992), Ferenc Erkel Prize (1997), Bartók–Pásztory Award (1998) just to mention the major ones.

Hollós’s works are regularly performed in European countries and some have also been played in the USA, Canada and Japan. He received several commissions from abroad. The most remarkable among them was for a piano concerto by the Oxford Orchestra da Camera for the 50th anniversary of the foundation of the UNO. He composed the Piano Concerto “Oxfordorian” which was issued on a CD with the Oxford ensemble. Chamber music has prevailed in Hollós’s oeuvre so far, but he has also composed oratoric, symphonic and choral works. Reviews regularly emphasize lyrical composition, the central role of melody, and the relevance of poetry as characteristic features of his style. Compositions published by Akkord offer a comprehensive picture of the fundamental trends of Hollós’s workshop from the 1980s to the present.

On the Edge of Non-existence is an early piece from 1985 whose inspiration goes back to Hollós’s student years as it was written in memory of his beloved teacher, András Pernye. The clarinet–violin duo was composed for the 5th anniversary of the tragic death of the musicologist whose ill health literally compelled him to “the edge of non-existence”. The employment of the clarinet is significant because it was Pernye’s first instrument which he had to give up because of the worsening of his health. The piece begins with an eight-bar solo clarinet passage and the clarinet retains its dominant role through the whole composition: the violin only joins in with countermelodies or it plays an organ-point to symbolize constancy and, at the same time, the inability to change. The associations one can perceive in the piece – for example, the 6/8 siciliano rhythm evoking the baroque tradition, or the note B and its association with the symbol of death as learned in Pernye’s lessons at the Academy of Music – pay homage to the musicologist. Rhapsodical Monologue (1990), another piece composed for the clarinet, lends an original perspective to the instrument. Composed for Pierre Albert Castanet, a French composer, musicologist and clarinettist, it reflects the many-sidedness and colourful interests of the dedicatee: it is built up of the permutation of various musical characters – calmo, dolce; scherzando; mistico and a repetitive character – and the typical motives belonging to them. These create exciting and often surprising contrasts in the structure of the work.

Other members of the woodwind family are also represented among Hollós’s works published by Akkord. In Floating Flute (2007) within 30 minutes we get fast glimpses of 28 short movements. Most of the movements, which are allotted poetic titles, were composed between 2005 and 2007. Exceptions are the paired movements Elegy and Like a Bird from 1984, which blend seamlessly into the series. The pieces in the series are eminently suitable for pedagogical purposes. The movements describe emotions and everyday activities (Careful Steps, Musing, Fear) making students of the instruments familiar with the expressive possibilities hidden in the technical capacity of the flute. There is a similar idea behind Six and a Half Flute Duets(1983–1992), which introduces instrumentalists into portraying characters as well as into the world of chamber music playing. The piece also expresses the question of the equality or subordination of the two parts. The composition of Oboepistola (1996) for solo oboe was inspired by oboist Béla Kollár. The piece, as indicated by the title, is a poetic letter, an epistle. Its main message is that traditional musical motivics did not become exhausted by the end of the 20th century and are still able to convey musical messages. This explains the dominant role of triads in the composition. Adagio ed appassionato (2000), a 10-minute piece in two movements for flute, violin and piano, manifests similar problems. In both sections of the work the fifth and the fourth have a central role in their perfect, augmented and diminished forms. The fundamental musical idea of the Adagio is the variation of downward or upward octave leaps and the arpeggiated incomplete chords within the octave lacking the third. The appassionato section starts with a sharp change in character: by then the ear had become used to perfect fifths and fourths, but in[1]stead here downward tritones are heard, fighting a playful rather than a diabolical battle with the perfect intervals returning occasionally from the first movement.

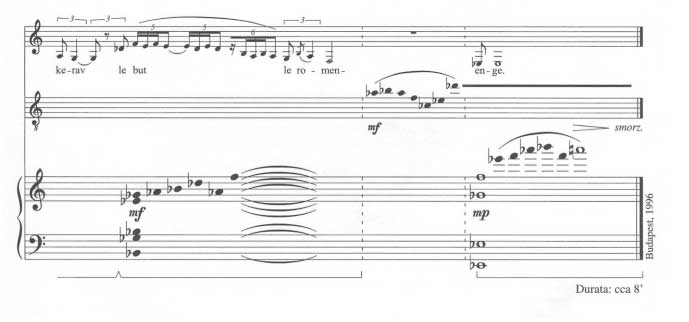

Two pieces, close in time and related in their musical problems in the technical sense are Căra luma phirav [I Wander the World] (1996) for clarinet or bass flute and piano, and a work for bassoon Dialogue with the Invisible (1997): the question is the coordination of the woodwind instrument, that is the human subject, and the part playing prerecorded and thus in a way alienated music. Yet a basic difference between the two works is that while the recorded part in the Dialogue is also a composition of Hollós so it does not leave the world of composed music, Căra luma phírav quotes folkloristic elements adding a significantly different meaning to the relation of the instruments and the pre-recorded material. The latter work was commissioned by the poet Károly Bari, who asked a few contemporary composers in 1996 to employ one of the Gipsy folksongs he had collected in a new composition, adapted to their own style. Máté Hollós selected a melancholic song, which describes the feeling of being an outcast. In the course of the approximately eight-minute-long piece the wind instrument takes over the original folk song tune, but in its rhythm it only roughly follows the free, pre-recorded vocal interpretation. After the first strophe the piano joins in and, with the variation of the folksong, the two instruments carry the musical flow to its climax. At this point all three verses of the song return from the recording with an enthralling utterance, and the two instruments join in again for the last strophe. The piece is rounded off with sensitive intertwining commentaries unfolding from the motives of the recorded folk song.

The message of the Dialogue with the Invisible is less dramatic. As the composer stated in an earlier interview, the recorded material is the voice of “the community of the past”. The relationship is far less tragic; it is a statement of the contrast between the subject and the surrounding world or unchangeable, closed history rather than a dramatic confrontation. In the absence of a recording, a keyboard instrument is suitable but in this case it should be placed out of sight behind a screen.

Three Pieces for Trumpet and Piano (1997) was published by Akkord with trumpet parts for C and Bb instruments. Although meant for pedagogical purposes, the pieces are also suitable for concert performance. The movements (Larghetto capriccioso; Largo arioso; Presto scherzante) get technically easier throughout the work and may be programmed separately as well. Trombondine (2013) is a solo piece for tenor or bass trumpet. It was commissioned by Corpus Trombone Quartet for their 2013 competition as a set piece.

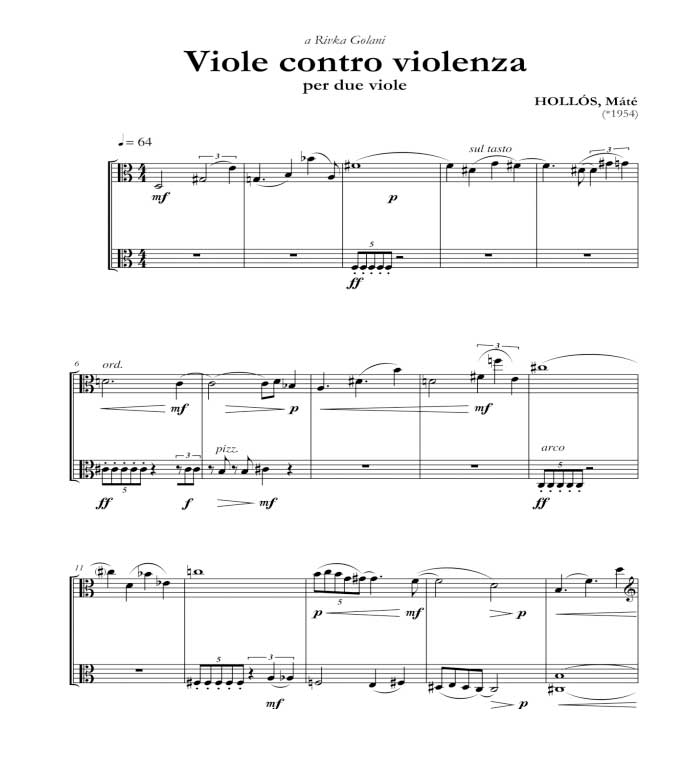

Among the works for strings Canto nostalgico (2003), composed for György Déri, is a dramatic monologue encompassing a large emotional scale which proceeds from the four-time forte of the opening note, successfully searching for the nostalgic melody named in the title, to the moment of the calming pianissimo ending. There is a pun hidden in the title of Inoa (2008) composed for two strings, violin and viola: a playful combination of the Italian names of the two instruments (violino and viola). Also in the same mode is the construction of Duo Violinetta: in its third, closing movement, fragments of the melodies from the first two movements return. Viole contro violenza (2010–2012) was also composed for two stringed instruments, this time for two violas, commissioned by the worldfamous Rivka Golani. It conveys a serious message, similarly to some other pieces which were composed as a result of the cooperation between the viola player Golani and Hollós. The double concertos for two violas and for viola and piano proclaim the importance of the search for peace, and they stand up for peace. Viole contro violenza is closely linked to the double concerto for two violas, it is even the same to some extent: it is to be performed as the first, third and fifth movements of the double concerto. In the remaining two movements the orchestra joins the two soloists. As a result of this unusual solution, the piece may be interpreted as a concerto divided by viola duos or a viola duo divided by orchestral interludes. The orchestral material can be hired from Akkord Music Publishers.

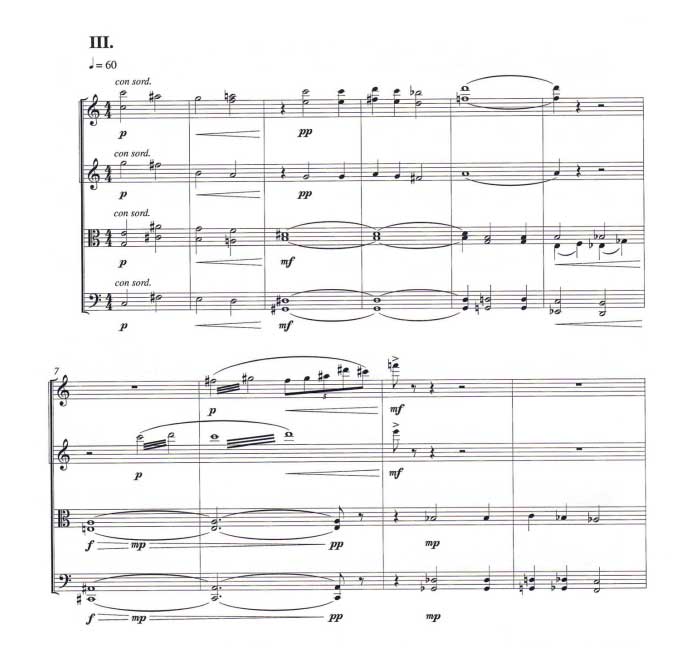

The two string quartets represent the most recent works of Hollós’s oeuvre. The definitive character of String Quartet No.1. from 2018 is its lyricism. The opening movement is dominated by soloistic manifestations and imitation; the instruments occasionally take over the melodic material from one another, varying the motives. The middle movement (Scherzo) is comic in its rhythm pattern with a clumsy, In stumbling 5/8 staccato. The final movement, in contrast with the linear structure of the first, emphasizes harmonic, chordal thinking.

String Quartet No. 2. (2020) the investigation into the possibilities of imitational technique and harmonizing suggest that the composer perhaps contemplated further the questions he put in the outer movements of Quartet No. 1 in a single through-composed work. 4–2–1 (2002) for piano four-hand was composed for the pianist couple, Ferenc Kerek and his wife, Éva Fekete. The enigmatic title refers to this. As the composer himself put it in the notes to the score: “Four hands, belonging to two persons and these two musicians are one soul when playing piano four-hand.” Looking closer at the score we realize that this is not only a turn of phrase: the structure of the parts often supports this: in certain sections the two parts are closely built upon each other, in others one pianist would be enough to play the parts divided among two. Impromptus for Julius and Japan (2012) was composed for the Gyula Kiss International Piano Competition, organized yearly since 2010 in Tokyo. 1 or 10 piano pieces (1994) contains ten numbered movements which are in such close motivic relation with one another that they may be considered as one unity. The closing piece rounds off the composition by repeating the first 18 bars of the 22-bar opening movement, then completing it.

The direct inspiration for Pezzo fisarmondiale (2003) came from Coupe Mondiale, the 2003 world competition for accordion organized jointly by Hungary and Slovakia. The president of the Hungarian Accordion Society commissioned Máté Hollós to compose a piece for solo accordion to be given its first performance at the gala concert of the competition. The five-minute long work presents the characteristic dance motives and typical sound patterns associated with the accordion in a new light with the extension of the tonal system and the unexpected phrasing patterns, as if placing them in inverted commas. The piece for three guitars or a guitar ensemble, Song for Many Guitars (1999), was also composed as a festival piece, commissioned for the László Szendrey-Karper Guitar Festival in Esztergom. The archaic sounds evoke an atmosphere of the past. Another piece for guitar, Farewell to Aase (2001), was composed at the deathbed of his mother. It was a set piece for both age groups in the guitar competition organized within the 2004 László Szendrey-Karper Guitar Festival. In the two-movement work the composer reflects on a special childhood memory and the poem At the Funfair in which his mother, the poet Eszter Tóth, recorded the event.

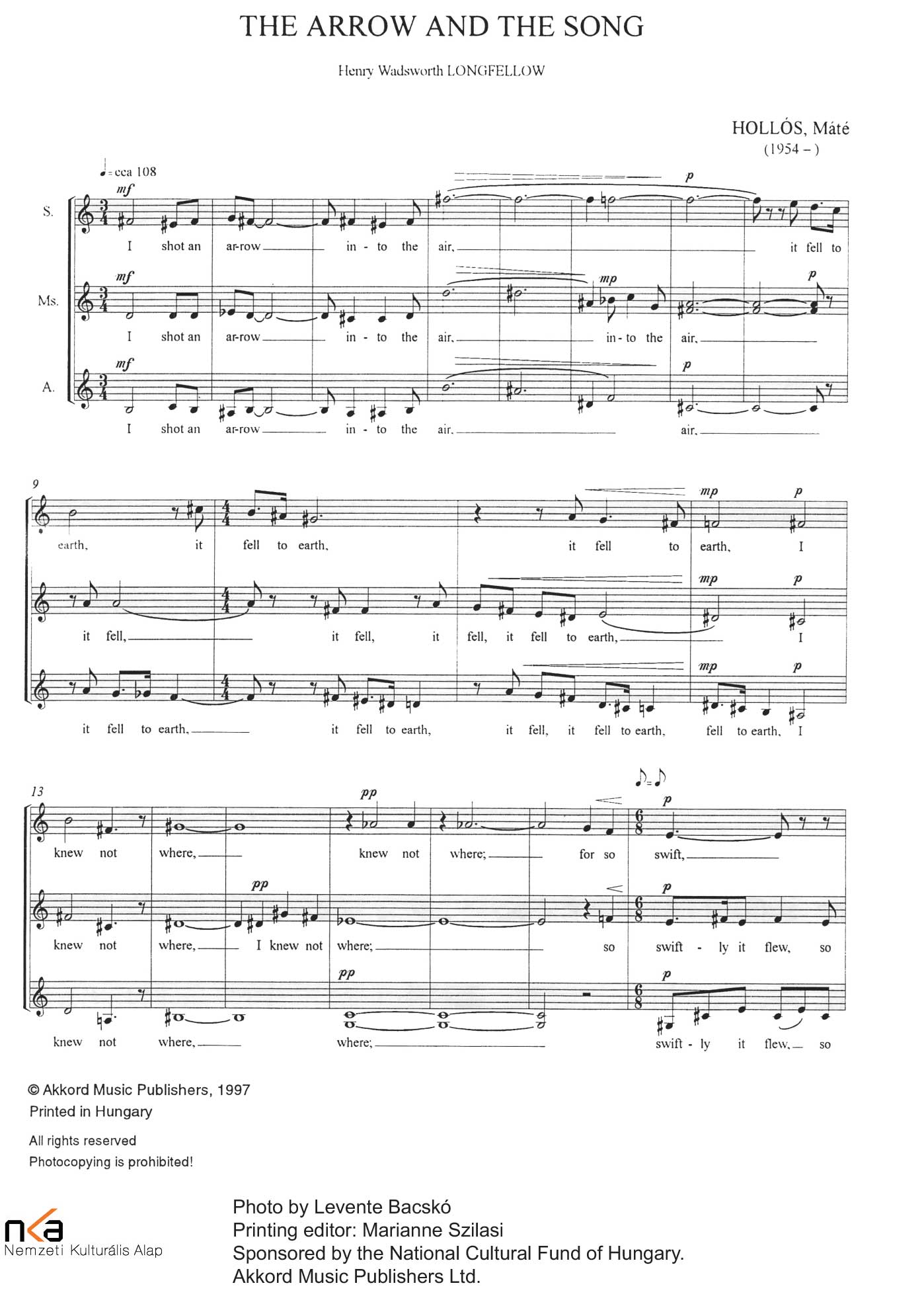

In addition to the instrumental works, two choral pieces with English words are also available at Akkord: The Arrow and the Song (1993) was composed for female choir and was the set piece in the finals of the Béla Bartók International Choir Competition in 1998. Lullaby and Song (1997) was also written for the same competition for mixed choir. Although published by Harpa Hungarica in Bloomington, two chamber works for harp are also distributed by Akkord. In Arpercussonata (2009) there are percussion instruments played by one musician in addition to the harp. Silent Trumpet Sound with Harp (1997) is a series of seven short character movements. The opening movement begins with a trumpet solo and the same thematic material can be heard in the last movement, this time surrounded by harp arpeggios. Then the listener feels as if the trumpet is further and further away, becoming quieter and quieter until the end.

Written by Viktória Ozsvárt

translated by Kata Ittzés